Learning from a Master Dealer: A. W. Noor Sher

by James Opie

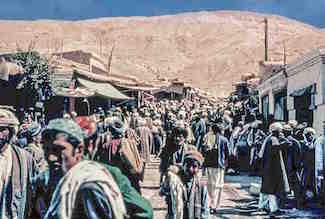

When I first met Abdul Wassi (A. W.) Noor Sher in 1973, he was the most successful rug dealer in all of Central Asia. In contrast, I was one of the smallest dealers in North America, a small dealer in a big jam. For I waited too long to arrange shipping all the goods purchased in Kabul, Mazar-i-Sharif and elsewhere during this first trip to Afghanistan, and had to leave for home the next morning. Only in fairy tales do “magic carpets” transport themselves. Preoccupied with buying from dealers who continually popped up with tempting offers, and with barely enough money remaining to pay my hotel bill, I neglected a vital part of my work. Facing this at such a late hour, could a single day possibly suffice to resolve my dilemma?

When I first met Abdul Wassi (A. W.) Noor Sher in 1973, he was the most successful rug dealer in all of Central Asia. In contrast, I was one of the smallest dealers in North America, a small dealer in a big jam. For I waited too long to arrange shipping all the goods purchased in Kabul, Mazar-i-Sharif and elsewhere during this first trip to Afghanistan, and had to leave for home the next morning. Only in fairy tales do “magic carpets” transport themselves. Preoccupied with buying from dealers who continually popped up with tempting offers, and with barely enough money remaining to pay my hotel bill, I neglected a vital part of my work. Facing this at such a late hour, could a single day possibly suffice to resolve my dilemma?

Shipping challenges in Iran had been simple. The Iranian “post” accepted twenty-kilo packages, wrapped in flour sacks or “gunee” (gunny sacking), addressed to me in the United States. I sent many packages this way, before my mentor, Hajji Rahimpour, began shipping quantities through the south Persian port of Khorramshahr. Using the Afghan post in this way was impossible, as regulations discouraged sending quantities of rugs and some pieces were room sizes, as large as 10 x 14 feet. A practical shipping method had to be found, and I had only one day to find it.

Mid-morning during this day a Kabul dealer who had sold me a half dozen pieces, responding to my plea, said, “Go Shar-i-Now. Find Noor Sher. Noor Sher know.”

It was easy to locate the Shar-i-Now (“New City”) district of Kabul and the name “Noor Sher” was familiar. Having heard this name spoken a half dozen times, always with tones of deference, I pictured a commanding personality, tall, with a strong voice. A man in his fifties or sixties.

Finding Noor Sher’s shop was not difficult but he was absent when I first entered. His brother-in-law, Walli, was there. Walli heard me out and said that, yes, Noor Sher could help me. Several hours later Walli and I moved all my goods from my hotel to Noor Sher’s shop and began measuring everything, to prepare export documents.

Halfway through this work, A. W. Noor Sher himself—not tall, but a short man with a quiet voice—appeared at the door in the company of a Turkmen. Noor Sher led the Turkmen—identifiable by his hat—to his desk, where the two spoke together earnestly. I saw Noor Sher hand across some money. A payment for goods? Perhaps a gift? I couldn’t tell.

Walli and I continued working as the two men drank tea. After twenty minutes Noor Sher escorted the Turkmen to the door. Walli then introduced me to Noor Sher and the latter invited me to sit with him at a desk cluttered with antique pistols and other artifacts. Calling to a teen-age employee, he ordered more tea before asking about my family---parents, children, wife. He asked if dealers had helped me to fulfill my goals in Afghanistan and if Afghans I had met treated me well. He made no attempt to interest me in his goods and did not mention an obvious fact: after not spending a single afgani in his business, I now appeared at his door, desperate for help.

Walli joined us to outline the terms of our agreement: shipping charges would be calculated and I could wire payment after returning home. There would be an export tax, plus “baksheesh” for customs personnel at the airport. A local transportation fee had to be paid and there needed to be a bit more baksheesh for that. As payment for managing all this Noor Sher would add his own fee of one hundred dollars.

Noor Sher smiled and said, “Very low price. Yes?”

Indeed. It was a fraction of what I expected.

Minutes later Noor Sher rose from his seat and pressed his right hand to his heart, and shook my hand. He mentioned my next trip to Afghanistan and asked where I planned to come first when I returned.

“To you!” I said.

He smiled.

“First go to hotel near me in Shari-Now.”

He wrote the name of the hotel, pointed in its approximate direction, and handed me the paper.

“Give taxi driver. First hotel, then here.”

“You promise?” he said.

I promised.

Ten months later I returned, and by 1975 Noor Sher and I were conducting steady business. A friendship took root, enhanced, surely, by hours spent with Noor Sher’s father, a retired rug dealer who often sat alone in an upstairs office. Noor Sher devoted as much time as he could to his father and I sometimes joined them, observing them discuss ongoing business. I always visited this old gentleman several times during my visits. Though he spoke as little English as I spoke Farsi, our exchanges were gratifying, and I knew they pleased Noor Sher.

From 1975 through 1978 I had a business partner named Bill and in 1977 Bill and I traveled to Afghanistan together, making a beeline for Noor Sher’s shop. We entered the ground floor office, decorated with rugs, Turkmen jewelry, Uzbek textiles and antique firearms. At that instant Noor Sher was beginning his afternoon prayers, a habit he maintained punctually, no matter who was present or what was happening around him. Considering the frequent presence of visitors, he prayed with a surprising atmosphere of privacy by pulling a rug from one of his piles, pointing it toward Mecca and beginning to pray.

From 1975 through 1978 I had a business partner named Bill and in 1977 Bill and I traveled to Afghanistan together, making a beeline for Noor Sher’s shop. We entered the ground floor office, decorated with rugs, Turkmen jewelry, Uzbek textiles and antique firearms. At that instant Noor Sher was beginning his afternoon prayers, a habit he maintained punctually, no matter who was present or what was happening around him. Considering the frequent presence of visitors, he prayed with a surprising atmosphere of privacy by pulling a rug from one of his piles, pointing it toward Mecca and beginning to pray.

Bill and I retired discreetly to one side and waited. After completing his rituals, Noor Sher welcomed us with the most radiant smile I had seen since my last visit with him. I introduced Bill and the usual questions about his family followed. I asked about Noor Sher’s family, and especially his father and with these essential queries completed I explained to Noor Sher that our luggage had not arrived but would come, we were told, in a day or two. To this prediction Nor Sher responded with a phrase he expressed often: “Inshallah.” (“If God wills it.”)

Whether he literally believed that everything, down to the level of lost luggage, depended on God’s will, I never asked. But he said “Inshallah” in many contexts, especially when a person voiced predictions regarding uncertain matters. The weather, the flow of business, the fate of nations all depended on God’s will. Even the timely appearance of our bags fell into the “Inshallah” category.

I asked if he might suggest a store where we could buy clothes to last several days and Noor Sher said nothing. Rather, he telephoned a tailor who came fifteen minutes later to measure Bill and me for loose, pajama-like Afghan garments. The tailor returned several hours later, our new garments in hand. When I asked for the bill, Noor Sher stepped forward.

“Not possible!” he said. He paid the tailor and, turning to Bill and me, brushed off our thanks.

Our first full morning in Kabul, dressed like locals but surely sticking out like sore thumbs, Bill and I began surveying the local market. Around lunchtime we returned to Noor Sher’s shop to find him standing on the sidewalk, hands clasped behind his back in a characteristic posture, with prayer beads dangling from them. The foot-high stack of rugs at his feet belonged to an Uzbek man who stood next to Noor Sher.

Our first full morning in Kabul, dressed like locals but surely sticking out like sore thumbs, Bill and I began surveying the local market. Around lunchtime we returned to Noor Sher’s shop to find him standing on the sidewalk, hands clasped behind his back in a characteristic posture, with prayer beads dangling from them. The foot-high stack of rugs at his feet belonged to an Uzbek man who stood next to Noor Sher.

I had met this Uzbek in Noor Sher’s shop during my previous visit and enjoyed watching him communicate with Noor Sher. Whatever engaged them—usually rug business but other interests, as well—the depths of attentive openness apparent in their exchanges revealed an admirable side of Central Asian culture. A friend who traveled there observed, “They pay attention to each other to degrees that rarely happens in the West, and this touches nearly every encounter. Even as one walks by an Afghan on the sidewalk, there is a silent contact. You can feel the Afghan holding you in his regard.”

Noor Sher’s Uzbek friend spoke some English and during our last encounter he shared the outlines of his difficult life and the history of many Uzbeks stuck on the wrong side of the prison-like situation in the Soviet Union. Only eight years earlier, the USSR’s forced atheism led this Uzbek to escape to Afghanistan. He immediately enrolled in a madrassa, a theological seminary, and visited Kabul often. He met Noor Sher, who began teaching the Uzbek how to deal in carpets.

Only a skilled poet could convey the unique look in this man’s soft brown eyes. Was it suffering or perhaps years of prayer that instilled such unusual depths? I saw great kindness and patience in these eyes, and understanding, as if this individual viewed life from a level above the rest of us. I have seen hints of this look in many Afghans, but Noor Sher’s Uzbek friend was unique. That he could also conduct business, buying and selling with the rest of us, amazed me.

The depth my enjoyment of such encounters was influenced by the writings of G. I. Gurdjieff, who traveled in Central Asia in the late 19thand early 20th centuries and wrote about “remarkable men” he met. I sometimes viewed the Pashtuns, Hazaras, Uzbeks, Turkmen, and other Central Asians I encountered as related, somehow, to Gurdjieff’s experiences. Whatever romanticism and naiveté flavored my outlook, the wordless strength of Afghans was real. These humane nuances had clearly been part of Central Asian life for extremely long periods; before the arrival of Islam in this region, with all its concern for how individuals treat each other, both Christianity and Buddhism had been influential.

The depth my enjoyment of such encounters was influenced by the writings of G. I. Gurdjieff, who traveled in Central Asia in the late 19thand early 20th centuries and wrote about “remarkable men” he met. I sometimes viewed the Pashtuns, Hazaras, Uzbeks, Turkmen, and other Central Asians I encountered as related, somehow, to Gurdjieff’s experiences. Whatever romanticism and naiveté flavored my outlook, the wordless strength of Afghans was real. These humane nuances had clearly been part of Central Asian life for extremely long periods; before the arrival of Islam in this region, with all its concern for how individuals treat each other, both Christianity and Buddhism had been influential.

Before heading north to explore markets in and near Mazar-i-Sharif, Bill and I saw Noor Sher often and I observed his knack for balancing generosity and shrewdness in conducting business. An expression of this was his talent for keeping a visiting dealer’s social calendar completely filled.

During our first hour together Noor Sher insisted that Bill and I “come to shop each day” for lunch. We agreed, but my tone of voice must have left room for doubt.

“You promise?” he said.

We promised.

These lunches, with an ever-shifting assembly of guests seated on carpets, served as a gathering point for diverse figures in Noor Sher’s business and social life. Dealers from several continents, an employee from a local foreign embassy, perhaps an ambassador, plus a Turkmen or Kirghiz trader, fresh from smuggling merchandise across the Chinese or Soviet borders, family members, and friends all sat on the floor around large trays of rice and lamb, unleavened bread, and regional delicacies. Noor Sher’s cook, a young Uzbek touchingly devoted to him, worked in a back room all morning, preparing this food.

A broad spectrum of communication styles characterized these meals, from the stillness of self-contained Afghans and other Central Asians, who often ate in silence, to talkative visitors from the West. During Bill’s and my visit a loquacious judge from California attended several meals and I recall a gradual shift among the English-speaking Afghans, from genuine interest in the judge’s remarks to a tentative receptivity, and then a subtle withdrawing of attention.

So many words…and during a meal!

Noor Sher said little but his presence potent. Listening carefully to everyone, he appeared to inwardly sort “the meat from the bones” with the same dexterity exercised with chunks of steaming lamb on his plate.

I came to see Noor Sher’s generous invitations to lunch as based on business acumen as well as generosity. Other dealers wished to invite me to meals, too, but Noor Sher left no openings. In short, he fed me and shared his world with me, and simultaneously cut out the competition. Evening dinners were approached the same way, with Noor Sher instructing key employees and family members to invite Bill and me to a succession of evening meals, or to his own home. When invitations came from other dealers, there was no room.

I came to see Noor Sher’s generous invitations to lunch as based on business acumen as well as generosity. Other dealers wished to invite me to meals, too, but Noor Sher left no openings. In short, he fed me and shared his world with me, and simultaneously cut out the competition. Evening dinners were approached the same way, with Noor Sher instructing key employees and family members to invite Bill and me to a succession of evening meals, or to his own home. When invitations came from other dealers, there was no room.

While he did not pretend to be more than a carpet dealer, a businessman, occasionally I heard Noor Sher address deep human concerns. He saw the center of any religion as residing not in books or doctrines, but deep in the heart of each individual. Though his devotion to the teaching of Mohammed was unequivocal, he viewed the inner reaches of Islam, Christianity, Judaism, and Buddhism as merging into one. At times he raised a single index finger, as if this said everything: One. And the prayer beads dangling from his hands were not a cultural ornament or distracting habit. His fingers moved the beads in a continual, silent, circumference.

As I picture my beloved friend now, decades later and with him no longer with us, Noor Sher slowly raises a single finger. One. And within reach of me as I write—sent most kindly by Walli after Noor Sher’s death—a string of his prayer beads.

He and I were born within months of each other in 1939. Yet I knew who the elder was, who the teacher and who the student. Never adopting a superior posture, he quietly communicated his understanding of business and of human nature, abandoning himself neither to judgments nor the need to be liked. Individuals in the West may make billions, but none can approach the artistry and humanity of Noor Sher. Although he sold so many rugs that entire cargo planes were sometimes chartered to transport goods to Europe, he accomplished all his buying and all his selling face-to-face, touching every rug he sold and looking everyone who came to him in the eye.

He did not pretend that business was unimportant to him but it always seemed to be what we would do later, after personal matters were attended. He asked many questions and when I mentioned this special talent, he said, “How you learn more, by talking or by asking? What more important, this new person learn about you, or you learn about him?”

Noor Sher taught me a great deal about conducting business in Afghanistan, or anywhere. All the while, as in transactions with Hajji Rahimpour in Shiraz, buying from Noor Sher lacked a characteristic feature of business throughout Asia, practiced with special intensely in Afghanistan: bargaining. If an English-speaking visitor tried to bargain with Noor Sher he shook his head and said, “Impossible.” Consequently, efforts to conceal interest in a rug, necessary in most transactions, were unnecessary with him. Avoiding temptations to peg prices according to the person in front of him, Noor Sher bought and sold in the market.Retail customers, including tourists, paid more than dealers, of course, but this was based not on an individual’s clothing or his credulity. It all was based on the market.

Noor Sher’s surefootedness and clarity of mind in this regard made it tempting to believe at times that he wasthe market.

The Oriental rug market in Afghanistan at that time was quite complex. There were new rugs, old rugs, and antique rugs. There were special purpose weavings for tents and yurts, new pieces, old ones, including antique tent bands and bags of many sizes, at times in excellent condition. Many used rugs revealed wear-and-tear, but of different degrees. Occasionally a rare piece was so distressed as to be a “rag”—yet in the right hands still valuable, and sought after. Most pieces contained traditional Turkmen designs, with repeating “guls” on red fields. Others displayed unexpected features, including archaic animal forms. Additionally, individual weavers expressed their unique skills through small alterations in patterns and additions that did not immediately meet the eye. Since weavers’ skills varied greatly, prices varied on this basis, too. Prices, therefore, could never be entirely standardized, even if bargaining was not the rule.

Dealing in commodities with so many variables, there cannot be one single “market.” Rather, there are intersecting, intertwining markets, according to the nature of the goods, what parties to a transaction know about them, and many other factors. Not surprisingly, some Afghan dealers did not operate “in the market” so much as they danced in its vicinity, sizing up a buyer and evaluating how much money he or she might have to spend.

Yet, all in all, disregarding the manipulations of both buyers and sellers, a real market,not dependent on all the individuals participating in it, touched everyone.

I labor this point because Noor Sher placed great emphasis on developing a clear sense of the amounts Afghan dealers willingly accepted, or paid, for various merchandise, that is to say, local wholesale values. Given all the differences encountered in ranges of goods, learning wholesale values was an ever-shifting, never-ending challenge. Sometimes the market was stronger, sometimes weaker. A major buyer having recently come from Germany to buy heavily inevitably left many contented dealers, and a higher market, behind him. All these factors, and more, contributed to these complexities. Yet a structure was discernible and I gradually began to comprehend it.

Islam offers many points of guidance for believers in their mutual relationships, including business exchanges. According to the Koran, prices will be set by the forces of supply and demand, but with an additional factor. Figuratively—some would say literally—Allah is always watching, and an individual helps or hurts himself through one’s own behavior. Perhaps this explains why dealing with Noor Sher was so different. In contrast, many Afghan dealers were better actors than they were Muslims and it was not easy to know when a dealer’s sincerity was genuine, and when it was contrived. In this regard Noor Sher shared quite valuable advice, related to a stage in the bargaining process. He insisted that when I had made an offer and a dealer began to fight hard, trying to force the price upward, I was to stand pat, refusing to budge by a single “afghani.” He said, “If you not offer reasonable price, dealer not talk so strong, work so hard. When dealer talk strong, never pay afghani more!” (An “afghani” was worth about two U.S. cents. This remains the Afghan currency and infusions of money from America support a similar afghani value today.)

Beginning to experiment with Noor Sher’s counsel, I immediately saved money. Often I was willing to pay more, but, remembering Noor Sher’s advice, when a dealer raised his voice or complained bitterly about my offer, I held firm. If he spoke English I might even say, “Aqa [sir], you surely will receive more from another dealer for this piece. Please, you keep it! Later you will make a big profit!”

Usually my offer was accepted after a bit more struggle and I left with the piece.

Arriving at prices inside Noor Sher’s shop was simpler, but with a twist. Noor Sher was busy with sellers from around Afghanistan and buyers from around the world and rarely gave off-the-cuff prices on pieces of interest to me. If I pointed to something when he was near and asked for the “gaimat,” the price, Noor Sher would say, “You like, we put aside. Later we speak price.”

By the closing days of our 1977 trip Bill and I had explored the market thoroughly and were reasonably attuned to values. Consequently, it was not difficult to estimate what most goods in Noor Sher’s inventory were likely to cost. With an antique rug or something especially attractive, I still did not know and could only guess. None of Sher’s employees dared suggest prices for anything and pleas for “ballpark” figures inevitably evoked the same response: “Talk Noor Sher. Talk Noor Sher.”

Bill and I waited until all the rugs interesting us were gathered. Then, late in our trip, Noor Sher made an appointment in an upper room where he would give the price of everything, one rug at a time, and we would make our decisions.

The hour of our appointment came and the session with Noor Sher proceeded comfortably. I was accustomed to Noor Sher’s preference for “yes” or “no” decisions, and his distaste for explanations regarding why a piece had been rejected. Prolonged hesitations were discouraged, and if I delayed too long he might say, “Jeem Opie…‘Yes…No.’” Pricing his rugs at realistic current wholesale levels and with stacks of rugs to go through, an experienced buyer was supposed to know the market and keep moving.

Noor Sher sat near Bill and me, indicating the price of each piece and we voiced our acceptance or rejection. While there was no bargaining, per se, several times I asked Noor Sher to lower a price slightly, as a favor, and he did. This was volume wholesale business and we both knew it.

Most pieces I purchased. Some I rejected. We worked for most of an hour this way, proceeding through several stacks of goods, when Noor Sher said abruptly, “Jim Opie, I tired giving price. You give price. I say ‘yes…no.’”

It was a startling challenge. Each piece was unique in its tribal or geographical origin, its age and condition. Aesthetic factors varied and the goods belonged to Noor Sher, who was absolutely attuned to values. Nonetheless, he and I reversed roles and I began setting the prices and the ground under me soon solidified.

After fifteen minutes, Noor Sher surprised me, and also Bill.

“Mr. Bill, now you name price and I say ‘yes…no.’”

This was surely an interesting moment for Bill, who understood that being tested is part of business. To suddenly be tested by Noor Sher was highly unexpected, and I was not sure who Noor Sher saw as the recipient of any “lesson” here, Bill as the primary participant, or me as an observer.

Bill tried to peg the price or two but quickly deferred to me. Soon, Noor Sher seized the reins again.

A life of “dealing” has not closed Noor Sher’s nature to a narrow opening, above which is carved the word, “money.” Rather, it opened him to a relaxed perspective wherein parties to a transaction experienced genuine concern for each other’s welfare. Beyond the fact that relationships of this kind feel good, more relaxed approaches to business encourage both sides to speak more candidly, sharing valuable market information. Freely shared information can be worth a great deal more than fleeting benefits.

Subtle but highly valuable benefits attend any dealings with exceptionally balanced human beings, and Afghanistan had, and still has, people I found to be superior in business. A lesson from Noor Sher I have tried to apply throughout my career is to approach relationships, especially long-term ones, in ways which balance my material interests, the other party’s material interests, and something in the relationship itself, akind of “neutralizing” force. For if we take our eye off the other person, we risk losing ourselves, too.

For our final evening meal in Afghanistan Noor Sher invited Bill and me to dinner in his family compound, an old fort. After we arrived Noor Sher absented himself for ten minutes to say his evening prayers and then joined us for a fine meal, cooked by his wife. Toward the end of dinner, Noor Sher’s six-year-old daughter joined us and stood next to her father, leaning her head on his shoulder. Noor Sher doted on this sweet girl, whose eyes shone like her father’s. He asked her to bring tea for all of us and, smiling, she set off, returning ten minutes later to pour our tea carefully.

As we sipped our final cup of tea—it was the very last enjoyed in Noor Sher’s company—he spoke about changes in the Afghan government and his feelings of deep foreboding. Left-leaning elements were, he said, “testing strength.” He said that while most politicians are “dogs of the same mountain,” – indistinguishable from each other in their motivations – the possibility of a Communist government constituted a serious crisis.

“If Communists come,” he said, “Afghans will fight.” In that eventuality, Noor Sher saw Afghanistan’s future as disturbing and uncertain.

Our conversation continued in this unhappy, prescient vein for a half hour. Our tea consumed, conversation subsided and it was clearly time for Bill and me to leave. We expressed our thanks and, chauffeured by one of Noor Sher’s household servants, headed back down the mountain to the Shar-i-Now district and our hotel.

The night was cold and the star-filled sky so reduced the urge to speak that Bill and I said nothing throughout our descent into Kabul. I could not know that I would never see Noor Sher in Afghanistan again, yet felt heavy-hearted. I recalled something he said: “Sometimes heart know more than head.”

Afghanistan’s status as one of the world’s most peaceful nations would soon change. After our return to the United States, a leftist, and atheist, government, aligned with the Soviet Union, took power in Afghanistan. As Noor Sher predicted, the tribes fought back. The Soviets invaded, ostensibly to protect a neighboring government, and the ensuing war turned millions of Afghans into refugees. Finally, assisted rather haphazardly by the West, the tribes and religious factions drove the Soviets out. Tragically, the addictive power of war survived the Russian’s departure, and the tribes and sects began fighting each other. From that point forward, a downward spiral continued, unto the present.

I did not return to Afghanistan for thirty-five years. In 2014 I traveled to Kabul and Mazar-i-Sharif to organize a “rug project” bearing my name. By then my friend Noor Sher had been gone for six years.

One day I asked the head of the family in Mazar-i-Sharif that works with me in our project if he had known Noor Sher. He said he had, and spoke with feeling of Noor Sher’s role in his younger life.

I noticed this man holding prayer beads in one hand, as Noor Sher always had, and I commented on this. My host understood but said nothing. Silently, he moved one bead at a time as we quietly completed our meal.

Some things in the Afghanistan do not change.

Questions or comments? Please email us.