Untitled

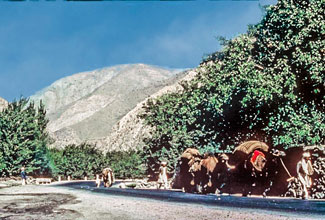

High in the Hindu Kush

Afghanistan lacks access to oceans and seas, a great disadvantage economically but a significant geopolitical advantage. Mountains and deserts form natural barriers to invasion, with some districts impregnable by land, including locales in the treacherously steep Hindu Kush range. (The name “Hindu Kush” refers to an incident centuries ago when Hindus, attempting to scale these challenging peaks, failed and lost their lives.) Further east from the site of this photograph, in Nuristan, ancient cultures, including descendants of Greeks from the time of Alexander of Macedonia, survived in isolated settings.

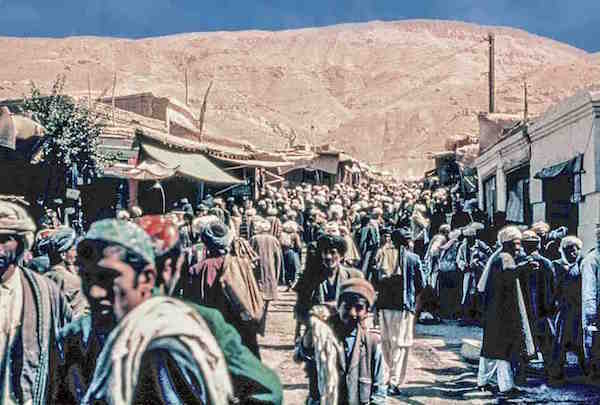

Market Day in a Town North of Kabul

The phenomenon of “market day” must date to ancient times, as these days were essential for farmers and craftsmen who needed to sell their products and purchase staples for family use. I always enjoyed market-day experiences and occasionally bought rugs, with little or no bargaining, from families who produced them.

Rural Farmers, Eastern Afghanistan (1974)

Riding a bus eastward from Herat to Kandahar, we stopped briefly at a small farm where several men were sifting grain. Note that the only factory-made item in this setting, a metal barrel, appears near hand-woven bins, used to store wheat.

An Afghan Shepherd and his Flock

For thousands of years, sheep have been bred in this region for the renewable “crop” they yield, wool, as well as for their meat. In much of the Middle East and Central Asia, grazing on lands with little vegetation allows rural communities to subsist. Deriving milk products and meat from goats and meat and wool from sheep, they trade some of these products for rice, tea, and other necessities.

Another Shepherd, Tending a Large Flock

An Afghan Nomadic Woman and Her Daughter (1977)

This woman and her daughter pitched their tent close to the camel bazaar on the outskirts of Kabul. The daughter stood at a safe distance as her mother twirled a ball of goat-hair yarn in a circle, applying “over-spin” to tighten threads for tenting material. I later watched the daughter gathering animal dung, used as fuel in their tent. For over a thousand years, little has changed in such corners of tribal Afghan culture.

An Unlikely Dyer

A man seeing me photograph a dyeing enterprise stepped into the picture, smiling. An actual dyer would never wear such a white garment!

An Afghan Dyer, with a Sampling of His Wares (1974)

I encountered this professional dyer in a side street in Kunduz, a city southeast of Mazar-i-Sharif in northern Afghanistan. Why he sat next to a birdcage stuffed with yarns I did not ask, and still cannot guess.

Untitled

A Primitive Nomadic Loom

In urban centers, weavers work on “vertical” looms. In villages and nomadic encampments, looms are “horizontal” and often on the bare earth. This image came from my first trip to Afghanistan, in 1973. While rigid steel looms are more common now, similar homemade looms, producing similar rugs, still exist there.

Teenage Turkmen Weavers, After School

The weaving of larger rugs is a social activity for Afghan women and teenage girls. Embarrassed and excited by my presence, these girls chatted and giggled while maintaining a swift pace.

Untitled

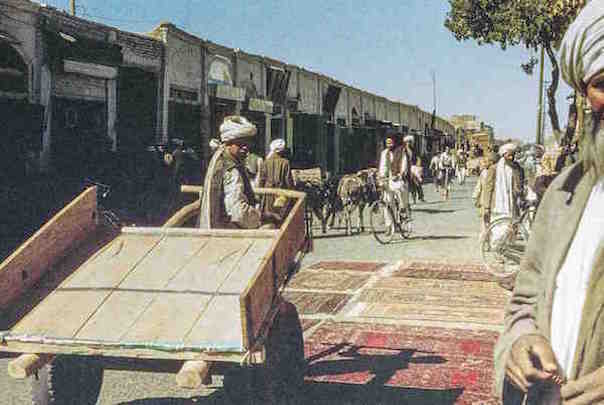

New Rugs Being “Aged” on a Street in Herat (1975)

Many rug dealers devised tricks to soften the colors of new, synthetically dyed rugs, making them look older and relaxing the “handle.” Another common aging technique, observed in both Afghanistan and Iran, involved spreading yogurt over the surface of a piece and setting it in the sun. This could be effective as lactic acid in the yogurt reduced the color intensity of synthetically dyed pieces. In 1975 all rugs from Afghanistan were synthetically dyed and no amount of pleading from dealers visiting from the West could induce a change. However, only one step separated the false “aging” of goods from the genuine article. That step was to return to using natural dyes. By the close of the 1970s several weaving enterprises were making rugs with all natural dyes. The trend, led by importers in the United States and Europe, is still gaining force, especially around Mazar-e-Sharif and Kabul.

Note that not a single car or truck appears on this Herat street. Today, traffic chokes urban streets throughout Afghanistan.

A Rug Dealing Family in Mazar (1973)

As suggested by pieces displayed by this family, Turkmen goods filled the rug market in Mazar-i-Sharif, with some Baluch goods. Most were newer but some inventories contained antique Turkmen and Baluch pieces.

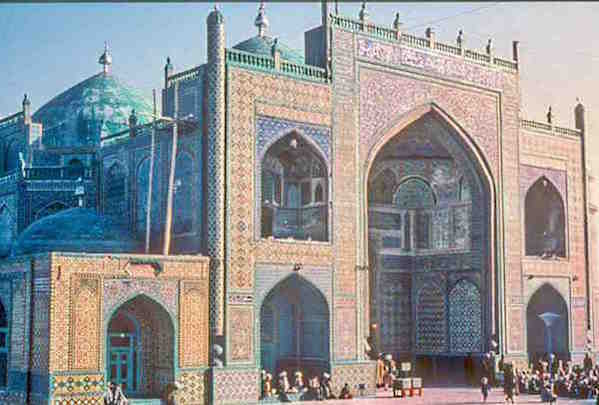

The Blue Mosque, Mazar-e-Sharif

While Hazaras are Shiite Moslems, most Afghans are Sunnis. The Blue Mosque remains an important Sunni pilgrimage site. Rebuilt in the 15th century after a long earlier history, the lovely building stands at the center of Mazar.

At the Kabul Camel Bazaar: A Face in the Crowd (1977)

And a very strong face, indeed. A military attaché of President Eisenhower, who faced soldiers at close range from many nations, reported the following:

Returning from an official trip to India during his presidency, Ike asked his pilot to stop briefly in Kabul. The purpose? To permit him to stand in front of an Afghan, taking his measure. In military and diplomatic circles, Afghans were renowned for not only pushing the British out, but successfully keeping them out. They likewise held off Czarist Russia, which conquered much of Central Asia in the 19th century. Afghanistan’s fierce warriors fascinated the President. Fulfilling this yen to stand face to face with an Afghan, the President did not leave a record of his thoughts.

Perhaps President Eisenhower encountered a face like this, marked by decades of challenges and with resolute depth.

”Nabi,” a Street Urchin and Tourist Guide (Herat, 1975)

Having heard that an American had checked-in the previous evening, Nabi, age nine, waited outside my hotel during my first morning in Herat. Eager to help, he stuck with me for several days and at the end of my stay even assisted in loading all the rugs I had purchased in Herat onto the top of a public bus that would carry me, and my cargo, eastward to Kandahar and Kabul.

Having lost both parents, Nabi slept in a mosque during warmer months and with an uncle in the winter and early spring. I only caught glimpses of other boys in his small urchin community, among whom he was a leader. Speaking fragmentary English, German, and Italian, whenever tourists or foreign rug dealers visited Herat Nabi made a living by showing them sights, performing errands, and playing skillfully on their heartstrings. Most Herat dealers I met knew Nabi and viewed my wish to pay him generously sympathetically. Once I bought an extremely dusty rug, which Nabi took to the center of the street to beat with his bare hands. He worked hard, with clouds of dust obscuring both rug and boy. Moments later a dervish fortune teller—every city had at least one—appeared and I paid him the equivalent of ten U. S. cents to tell my fortune. For the same amount he also told Nabi’s. War was nowhere on Afghanistan’s horizon at the time but the dervish unequivocally saw soldier in Nabi’s future. A sad prophecy, I thought, but surely true.

For several years I sent sums to a rug dealer in Herat who kept an eye out for Nabi. My intention was for him to dole out small amounts to the boy, and I suppose this worked out fairly well. By 1979 I lost touch with him. And then the Russians invaded. During the following years, was Nabi a Mujahedeen hero? A victim? Both? I never learned. This image of him still warms me, but saddens me, too.

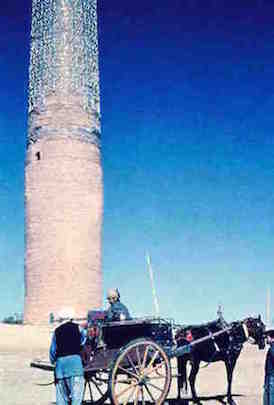

A Minaret on the Outskirts of Herat

Herat, Afghanistan, not far from the Iranian border, was once one of Asia’s great artistic centers. During that era, Islamic art and religious studies—and true spirituality—went hand-in-hand. Several great mosques in and near the city now have only walls or minarets to remind us of formerly magnificent structures.

The taxi driver in this picture was, for a moment, my young friend Nabi. With good humor, the driver let Nabi take the reins to try his hand at managing the horse. I also tried. It’s not so easy.

A. W. Noor Sher and James Opie Wrap Up Their Business (1977)

Among my essays is writing devoted to my late and dearest friend, Noor Sher. A clear-minded and cheerful person, Noor Sher was shrewd and highly successful. For a time, he handled more rugs than any other dealer in Afghanistan, and probably all of Asia. Personally overseeing a constant flow of buying and selling, he remained straightforward and humane, sharing his knowledge of business and his bountiful “table,” with scores of western dealers arriving in Afghanistan by air or by land and making beelines for his store. Over time Noor Sher and I came to share a rich friendship, beyond the framework of business that initially drew us together.