Nabi

by James Opie

I met Nabi, a nine year old street urchin, in Afghanistan’s northwestern capital, Herat, in 1975. By day Nabi kept company with anyone who would pay or feed him, but especially visiting foreigners, including rug dealers like me. His local network must have included staff members at my hotel, as he knew an American was there, even before he saw me. He waited outside the hotel during my first morning in Herat and called to me as I walked down the front steps.

I met Nabi, a nine year old street urchin, in Afghanistan’s northwestern capital, Herat, in 1975. By day Nabi kept company with anyone who would pay or feed him, but especially visiting foreigners, including rug dealers like me. His local network must have included staff members at my hotel, as he knew an American was there, even before he saw me. He waited outside the hotel during my first morning in Herat and called to me as I walked down the front steps.

“Hello! You American! I help you!”

He reached for my briefcase, smiling broadly.

“I Nabi. I carry this for you!”

With several thousand dollars in local currency in the briefcase, I declined his offer. I enjoyed Nabi tagging along, however, and trusted him when he said he could direct me to a street with half a dozen rug dealers. As we walked together, I mulled over similar experiences in Turkey and Iran, warning myself to be cautious. No matter the age of the “helper,” these offers usually led down winding, manipulative paths. An uncle with a shop . . . . A cousin who sold at low prices and loved Americans . . . . There was always a story. Yet, without question, Nabi’s outgoing personality was working on me. Watching him stride confidently next to me, but noticing the state of his clothing, it occurred to me that he might be parentless.

“Do your parents live near here?” I asked.

“First father sick; die. Mother sick, die. Mother with sister die.”

I expected him to be an orphan. But had he lost a sister, too!

“Your sister also died?”

“No, mother-sister.”

“So, your mother’s sister became sick and died?”

“No. Mother die with mother-sister. Mother-sister not die. She move to Zabol.”

Thus I learned of Nabi’s central tragedy.

Nabi added that his aunt and uncle traveled from Zabol to Herat every few months to see him, but his sole relative in the city was an uncle who begrudgingly took him in only during winter months. I was there during the fall, when daytime temperatures were still warm.

Just ahead of us was a small chiahana, a tea house. Since we were in no hurry, we stopped in for tea. As we sat together, I noticed that when he faced me Nabi smiled. As he turned away, his expression changed. I caught glimpses then of a deep sadness one would anticipate in such a deprived young life.

Looking my way, the cheerful Nabi reappeared.

After tea, Nabi carried our glasses to the kitchen, found a wash cloth and cleaned our table—not gestures of a professional beggar.

Only two nights before, in the Iranian city of Mashhad, I had discussed styles of begging with a rug dealer fresh from visiting India. He described the antics of professional beggars there who ran an entire enterprise around renting babies. Carried by a begging older child, the babies were trained to reach out as if hungry. A “good” rented baby whimpered enough to attract attention, but not so much as to become a pest. Afghanistan also had many beggars, but no begging syndicates, such as this dealer had seen in India. Giving to the poor is ingrained in Afghan culture, though the amounts given may be small.

Nabi’s dirty, tattered clothes were a clear indication of his parentless status. And his hands . . . . In the tea house I asked to see his hands and was shocked. They looked more like soiled leather than a child’s flesh.

He slept, he said, in “the mosqee,” with other boys, also homeless and parentless.

Decades later, during America’s major military involvement in Afghanistan, I read about the country’s desperate poverty and high child mortality rates. In words expressing her alarm, an American visitor in 2008 reported that twenty-five percent of children died before the age of four. This reporter, unfamiliar with Afghanistan, saw evidence of a cultural breakdown, due to war. I had a different view. Twenty-five percent was exactly the child-mortality figure I had heard during my visits in the 1970s.

In 1977, before the Russians invaded, I spoke with a man who worked for the Ministry of Health in Kabul. This gentleman, a friend of my colleague Noor Sher, saw Afghan health officials as clear-minded in not accepting international medical assistance for certain diseases. His reasoning: although Afghanistan’s food resources were limited, there was no starvation. Unchecked population growth could lead to fighting over resources, and social unrest. Resulting instability would be harmful to everyone but “warlord” types, who thrive on discord.

I didn’t know what to make of these opinions and the deeply rooted problems related to them. The only practical solution I have found is to provide employment in a traditional industry for as many adults as possible. In Afghanistan, those who ask for help are rarely refused totally. Trusting those with jobs to be kind to citizens in greater need strengthens the society.

As Nabi and I left the tea house and returned to the street, we were approached by several friends of Nabi’s who, he said, slept in the same “mosqee.” Though I stood merely inches from them, I retain no clear pictures of these children, who obviously looked to Nabi for guidance. Perhaps I hadn’t wanted to take in what I was witnessing. A nine-year-old guiding the lives of others his age....

After consulting with Nabi, the boys went on their way.

Nabi knew the first dealer we visited, who welcomed him cheerfully. From the outset, I made it clear that Nabi’s presence would not influence any prices I might pay. (In Asia, in nine out of ten instances, a person who takes you to a dealer receives money under the table—a custom I deliberately chose not to follow.) I said I would give Nabi baksheesh separately.

Nabi understood me. Pointing to the dealer he said, “He no pay me. Maybe you pay...okay.”

After Nabi helped tag and bundle the few pieces I bought from this man, we moved to the next dealer. He also recognized Nabi, who sat to one side on a low stool, watching us until his services were needed. As I often did on my first visit to a shop, here I began bargaining over a rug I really did not want. Why engage in this ploy? Making an offer I knew was too low freed me to observe the dealer’s bargaining style. Would he dismiss my offer silently, perhaps with a dismissive head shake? Would he make a counter-offer? And if he did, would he (as I anticipated), perceive I was conversant in the local market and thus was not a push-over?

Conducting business so far from home is, at best, an insecure proposition and every small insight gained is helpful. I came armed with the local words for “I am not a tourist,” (“Toureest neestam!”) and other helpful phrases, especially the words for “Expensive” and “Extremely expensive!” All this may seem like a game, and for tourists, it is. But when you make a living this way it is not a game.

This second dealer was an easy-going man with straight-forward pricing. He specialized in Baluch rugs and buying half dozen pieces from him was enjoyable.

As we prepared to leave this shop, a dervish fortune teller appeared. These men are a fairly common sight throughout Afghanistan, often traveling from town to town, village to village, making a living on scattered populations. True dervish orders have existed in Afghanistan from ancient times, and Sufi schools continue to function today. But modern dervish fortune tellers are a breed unto themselves, having little in common with serious dervish pursuits found elsewhere in Asia, requiring group work under guidance of a teacher.

These fortune-telling dervishes can be identified by the colorful strings of beads around their necks. Hired to tell a person’s fortune, they manipulate the beads with their fingers, appearing to enter a trance-like state in which they can see beyond day to day levels of reality.

Paying the dervish the equivalent of about ten U.S. cents for each of us, I asked him to tell my fortune and then Nabi’s. In Nabi’s future, he unequivocally saw “soldier”—a sad prophecy, perhaps, but probably true. Although war was not on the horizon, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan only five years later. Nabi readily accepted his “fortune.”

“Yes! I be solder!” he said, as enthusiastically as many boys his age would.

At lunch time, Nabi and I found a small restaurant selling kabobs and rice and I insisted he wash his hands before eating. Afghans meticulously follow their religion’s dictates regarding cleanliness, but with neither parent nor guardian to guide him, Nabi needed instruction. When he returned to our table, I checked his hands—still dirty. Feeling that some “parenting” could be helpful, I instructed Nabi to wash again, which he willingly did. The result was the same. I watched as he washed a third time, seeing that the problem wasn’t his technique or the soap. It was his soiled, leathery skin. Nabi wanted to show me truly clean hands. It just wasn’t possible.

After staying by my side that entire day, Nabi saw me to my hotel in the evening. The next morning, he was there again, waiting to greet me and I was pleased to have his company. As we approached our first rug shop that morning, however, Nabi held back. Instead of entering with me, he stayed a few yards outside the building. Looking out the window, the dealer owning this shop saw him waiting and surmised the situation. “You help bad boy! Should not give money! Not go to school! Always live with bad boys!”

This outlook, expressed in such negative tones, upset me. Then, I wondered: could truth be on his side, however sour this man’s attitude? Could I unintentionally be contributing to Nabi’s delinquency?

Since none of this dealer’s goods attracted me, I quickly moved on to another shop, with Nabi again at my side. This dealer, in his late twenties and speaking excellent English, also knew Nabi and clearly liked him. With Nabi standing close to us, I quoted the negative remarks I had just heard.

“Always this man criticizes, but what does he do to help these boys? Nothing! Yes, we all know it would be better if they went to school. But who will wake them up in the morning? Who will help them get ready for school? Who will feed them not just some days, as many of us do, but every day? Who will see that they are clean? And who will stop other boys from teasing them in school? You know how some children can be. Look at the clothes boys like Nabi wear. Who will give them clean clothes? Who will give them clothes that fit?”

He was quiet for a few moments and I began to look around the shop. Kneeling beside me, helping sort through a pile of rugs, the young dealer continued. “It’s sad to see the boys living this way. Who does not wish they had families to care for them? But, think about this with me. Maybe these boys do go to school, in a way, here in the middle of Herat. In the school of Herat they learn a lot. You may not know that Nabi say “hello” and a few other things in six or seven languages. And he speaks quite a bit in English, Italian and German. It’s true, not every dealer from Europe or the States wants to be with Nabi and boys like him. But some do. Maybe these young boys who bother this other dealer so much are going to school, in their own way.”

Gesturing in the direction of his neighbor, he added, “ In my opinion, men like this only want to criticize, not help. I have heard this man speak to his wife with a voice I would not use in chasing away a dog.”

All the while, Nabi listened dispassionately. And, wherever we were, he looked for opportunities to work. Later that day, after asking him to “dust” an incredibly dirty rug, I observed him as he carried it to the center of the street—there was no traffic, not a single car—and beat on it for all he was worth. The cloud of dust obscured both boy and rug for moments and I had mixed feelings for having put him through this. Yet, he clearly liked to be useful.

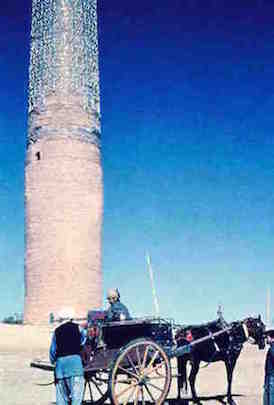

Nearing the end of my stay in Herat, I didn’t want to miss visiting the remains of one of Central Asia’s great classical mosques, with only a lovely tiled minaret still standing. To get there, Nabi and I hired a horse-drawn taxi. These must still exist in Afghanistan, though I saw none in Kabul or Mazar-i-Sharif during my recent visits. (American development billions have been converted into so many automobiles! The streets are choked with them.) In the 1970’s, motorized taxis were the exception, and horse-drawn taxis the rule. Extremely few citizens owned cars.

As we approached this once-great edifice at the far edge of Herat, Nabi asked the taxi driver if he could take the reins. The driver cheerfully let him struggle with a horse suddenly uneasy under Nabi’s unskilled hands.

As we approached this once-great edifice at the far edge of Herat, Nabi asked the taxi driver if he could take the reins. The driver cheerfully let him struggle with a horse suddenly uneasy under Nabi’s unskilled hands.

During our return to town, Nabi tried to tell me about an event he wanted to attend that evening. Since I couldn’t understand him, we hurried back to the young dealer who spoke good English. Fortunately, his shop was open and, listening to Nabi’s animated remarks, the dealer explained: “Tonight there is a circus in Herat, not far from your hotel. Nabi would like to go and hopes you will take him.”

With coins in hand and me not far behind, Nabi did go to the circus. As he pressed his way into the small white tent, with a pointed top and broad flaps of fabric staked to the ground, I tried to follow, but the entrance was so tightly packed I couldn’t elbow my way in. I lost sight of Nabi, but felt satisfied knowing he was part of the laughing, applauding crowd inside. Later he surely found his way home—the “mosqee”—on his own.

Listening the next morning as Nabi spoke excitedly about his experiences, I could make neither head nor tails of what he was saying. He had fun! I understood that much.

On that last morning in Herat, Nabi helped load the stacks of goods stashed in my hotel room onto the top of the bus that would take me on to Kandahar, and then Kabul. I paid him well and tried to make less of our goodbye than I felt. I had two lovely children back home and...Nabi? With no parents and no permanent home, he seemed extraordinarily deprived. Yet, I had witnessed support flowing his way—some money and food, but also interest, engagement, kind looks, kind words—from dozens of adults, enough to sense that the city of Herat indeed had a “social safety net.” This was, after all, Afghanistan, a profoundly Muslim nation where charity remains a central virtue. I reflected, too, that Nabi’s life was, to say the least, interesting, as many lives at the margins are. He had learned to fend for himself, to “hustle,” in a constructive way.

We have a word for people like Nabi: “survivors.” We naturally admire them, even when wishing their lives could be different.

I left money with the young dealer who spoke excellent English, to dole out to Nabi every now and then. This dealer and I communicated through the mail for several years before he moved to Europe and I lost touch with him, and thus with a remarkable boy.

Whether or not Nabi is alive, I do not know.

What happened in Afghanistan after the Soviets invaded was an extraordinary test for the nation, and for even its hardiest “survivors.” Yet something in all this, in the courage Nabi asserted every day, in the outlooks of adults who cared for him, and other children like him, surely lives on. Perhaps what we feel when reflecting on youths like Nabi are also threads in a vast, living fabric. As a sage once said concisely: “Nothing lasts forever, or ends completely.”

James Opie

Questions or comments? Please email us.