Good Driver

by James Opie

I sat in an aisle seat a few rows from the front of the plane and through the pilot's open cockpit door saw a vast, inviting view of an orange-tinted Central Asian dawn. I approached the cockpit and said to the pilot, “You must see many spectacular sunrises.”

“Yes,” he said. “If you want to see a lovely one this morning, you are welcome to sit here.” He gestured toward the empty co-pilot's seat.

Thus, miles above the earth, I was introduced to an extraordinary nation: Afghanistan. When I hear this name mentioned now memories from that first visit in 1973 come to mind. The same land, the same peoples, the same varied languages exist today, under the same flag. But decades of strife have altered a nation that never invaded anyone, and never sent its sons to the West on terror missions. Today, hints of the former depth of human character, a mix of innocence and worldly wisdom so appealing to visitors, can still be encountered. Perhaps one day a peaceful, welcoming Afghanistan may exist again on its territory. Support for this possibility, and at least providing work for weavers desperate for employment, is central to my Afghan Rug Project.

I began buying rugs there on a shoestring, seasoned by a few trips to Iran but with little money and no contacts in Afghanistan’s rug markets. Friends in the industry who had traveled there spoke of extremely low prices, and this appealed to me, of course, given the insecurity of my business, which needed all the help it could get. I was, therefore, braced for challenging bargaining sessions in pursuit of deals. But no one prepared me for the final moments of that first flight. Before landing in Kabul, the aircraft and its sixty passengers remained well above mountain peaks until the last second before descending so rapidly it felt we were not flying, but were falling to the ground! As the plane leveled again, I felt reassured and the landing was as smooth as silk.

A coup had ousted Afghanistan's king only three weeks earlier and I had no idea what to expect. Would soldiers ring our plane? Would they search us? Perhaps hold us in the airport for hours?

Only a dozen soldiers manned the small terminal and, beyond stamping my passport, no one noticed me. Outside I saw hints of instability: near the taxi stand, a single tank with an open hatch sat silently. On top of the tank, a soldier enjoyed a morning smoke.

I used Farsi phrases learned in Iran to bargain with the driver and described the class of hotel I needed: a decent local one, not an international hotel, and not expensive.

“Parwan nist, mister,” he said. “Hotel haile garunee nay.”

“No problem, mister. Hotel not expensive.”

Most Afghans are naturally helpful and the driver took me to precisely what I wanted: an inexpensive hotel near the Kabul River, next door to a theater with posters depicting Indian actresses clad in saris. After dinner in the hotel, bone tired, I headed for bed and was asleep by 9 p.m.

My rest lasted only a few minutes when roaring voices outside shocked me awake. I peeped out the window and saw the heads and shoulders of a cacophonous crowd of men and teenage boys moving down the street. In my jet-lagged state a single notion explained what was happening: a counter-revolution!

I ducked below the window to remain hidden, bobbing up for half-second looks over the windowsill, tracking the noisy mob as it spilled onto the main street, parallel with the river. Alert for the sound of tanks and gunfire, I only heard the crowd; still moving below my window.

When all was quiet I went downstairs to the reception desk where a night clerk sat drowsily. When he was alert I asked what on earth was happening outside. Was there another revolution?

The clerk didn’t understand me at first and when he did he laughed. All this noise was simply an over-stimulated crowd of men and boys, leaving the theater next door. The movie, he said, included women with their faces uncovered, and their arms, too!

“Very exciting!” he said.

There was no counter-revolution, but merely sex energy, channeled into human voices.

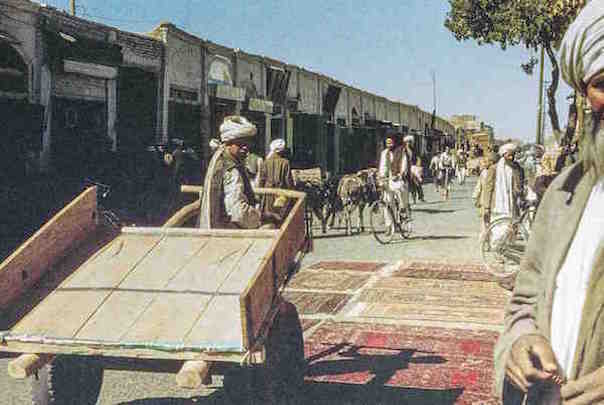

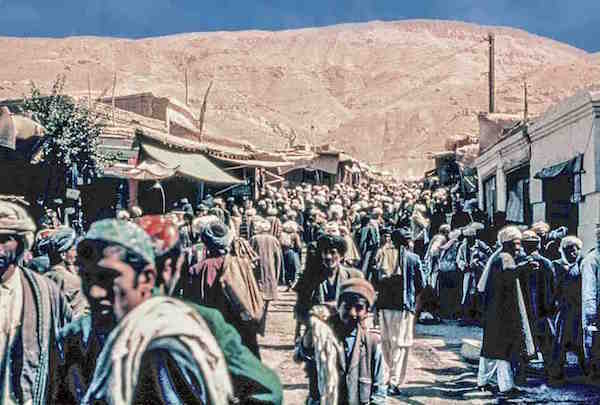

The next day, I began exploring Kabul's older rug market, located opposite the bushkasi playing field in the oldest part of the city. I had been advised to buy nothing at first, but simply look, and followed this advice, adjusting to an entirely unfamiliar market. In the middle of the afternoon I took at cab to another market center near “Chicken Street,” in a district of Kabul known as Shari Now—“New City.”

Prices for goods on-offer in both markets seemed decent but not amazing, and I held back from buying anything. Several dealers back home had spoken excitedly of buying Turkmen rugs in northern Afghanistan, in and near Mazar-i-Sharif, at surprisingly low prices. Around Mazar, they said, prices were at least thirty percent less than could be found in Kabul. Eager to encounter the real prices, I set my sights northward toward Mazar.

There were three ways to get there: fly in a Russian-made Yak-40 plane that usually landed safely, ride in a bus shared by villagers (and their poultry), or rent a car and driver. The car-and-driver method cost fifteen dollars a day—not cheap. But a car included a major advantage: keeping close company with my goods during the return to Kabul. Hiring a car, rugs could be packed into the trunk and on the back seat.

The driver I hired spoke some English, for which he charged another fifty Afghanis a day—about a dollar.

We spoke little while traveling north and I greatly enjoyed the fresh, exotic scenery. We passed though mud villages and stopped several times for tea. In one town, market day was in full swing and we stopped long enough to make my first purchase: a rug about three feet by five, with a field decorated by tall human figures. The man sitting on this rug said his wife had woven it. He asked the Afghani equivalent of thirteen dollars for it.

This price was very low and I wondered, “Did I hear him right?”

I asked the price and heard the same figure again. Now . . . dare I bargain?

Of course! This was Afghanistan! One must always bargain. Right?

Wrong. Knowing when not to bargain is part of the craft. Thus I failed a small test by offering eleven dollars for the piece and encountering a brick wall. This seller did not bargain! I thought about what this rug would cost me in Iran; fifty dollars, at least, and perhaps sixty.

I purchased the rug for the asking price and returned to our car, pleased with my first solid buy in Afghanistan.

As we entered the Hindu Kush range the driver began our uphill ascent through short straight stretches and many twists and turns. Each curve rendered views of snowy peaks above and deep green valleys, far below.

As we arrived in Mazar-i-Sharif the driver allowed a camel caravan to pass in front of us before dropping me off at Mazar’s government-owned hotel. A desk clerk led me to my cavernous room—large enough to house a sizeable Afghan family. An hour later I found a restaurant near the hotel where half the men engaged in their prayer rituals: standing, kneeling, touching their heads to the floor. The other half, presumably having completed these rituals, were eating. Laughing and talking as they ate, this cluster sat in the circle on the floor, near the praying contingent.

The seamless integration of the two worlds, one centered on prayer and the other on life’s daily needs, characterizes so much in the life of Afghanistan. Here, Allah is distant and present, ever-present and ever-distant, in every everyone, in every event.

A teenage waiter took my order of “morgh wa chello” (chicken and rice) and I peered into the kitchen whenever he entered and exited. There were no women among those eating their dinners and no women in the kitchen, either. Thus far I had seen only a few women walking on the edge of streets in Mazar-i-Sharif.

“Surely there are women somewhere,” I thought. “Otherwise, could there be any men?”

This was truly pre-modern Afghanistan, without television, and with far more horse-drawn conveyances on Mazar’s streets than cars.

I rested well that night and the driver appeared in the hotel lobby on time the next morning. He drove me from one cluster of dealers to another and remained close throughout the day, watching me bargain and making occasional comments. He knew nothing about the rug business but understood the bargaining process quite well. He understood, therefore, my insistence that we “walk out” and even drive away, whenever bargaining reached an impasse. (We could—we did—return to the same shops later, and the prices went down.)

During our three days in Mazar I visited at least thirty dealers, buying dozens of rugs. Most were fifty to seventy years old, but several Turkmen rugs were true antiques. One, a Chodor main carpet, was sold several months later to a New York dealer for a triple profit.

After we concluded our final transactions in Mazar the driver and I began the long drive back to Kabul. By then the trunk was packed so full the driver barely could close it and the back seat was mounded to the ceiling. I even had rugs and bags crammed between my legs and feet.

As we headed south we returned to the steep terrain of the Hindu Kush, with sheer cliffs dropping off abruptly yards from the edge of the road. Continuing this way, about two hours south of Mazar-i-Sharif we came upon a startling scene: a public bus crashed into an enormous rock on the right side of the road. Passengers in clusters showed no signs of injury, which was surprising, given the drastic state of the bus. My driver slowed, but not too much, as several dozen bus passengers approached our car, begging for rides.

My driver said, half under his breath, “Not possible.”

As we passed the bus and saw its entire front end smashed against a house-sized boulder, my driver exclaimed, “Good driver! Good driver!”

We regained speed and traveled another kilometer before I spoke.

“You said, 'Good driver…’ Please tell me what is good about crashing a bus full of passengers into a huge rock.”

The driver did not immediately respond. About a kilometer later he said, “You not understand. Driver lose brakes. Bus will crash. It must! Where crash? Driver need decide. Not easy decide! Easy…wait. Easy, not crash. Then bus goes much fast! If crash up here, some hurt, but no one die. There,” (he pointed down the mountain) “many die. Maybe everyone die!”

His smile was impersonal, not directed to me, or anyone. He smiled broadly as if relating to a deep understanding deep within himself, and said again, “Good driver!”

We were silent for the remainder of our trip to Kabul, even when stopping for tea. Perhaps my driver was organizing his thoughts, but regarding this I could only guess.

After helping me unload my goods at the same Kabul hotel, he gestured for me to sit with him on a low stone wall, where, as I soon understood, he wished to express . . . final remarks.

“You young man,” he said, “not realize, sometimes better crash early, when damage not great. Sometimes you wait and wait; damage very great! In life, must know . . . when crash.”

He looked at me intently, as if his eyes might convey this lesson to a place within me that only more experience—much more experience, in Afghanistan, in Iran, and back home—would bring to the surface.

James Opie

Questions or comments? Please email us.